Holistic Stream Assessment/Restoration: Trout Brook - Dover, Massachusetts

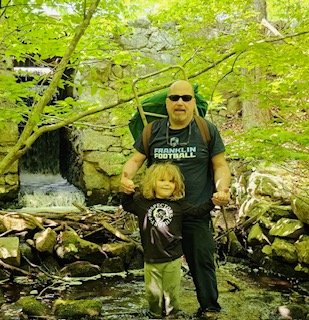

Trout Brook at Haven Street.

“trout brook without brook trout would be a tough pill to swallow”

big picture thinking

Native Fish Coalition has undertaken an organization-wide project to develop a methodology to address stream assessment and restoration. The approach is holistic and requires a complete assessment, analysis and understanding of the situation before any recommendations are made or any action is taken.

While the assessment phase will require a lot of manpower, costs will be low as NFC will utilize volunteers, and help from other organizations and government agencies. The restoration phase is where the money is spent, and our goal is to maximize the return on investment by looking before we leap…

This “big picture” approach represents a paradigm shift in regard to what is often symptom-centric aquatic ecosystem restoration. While it will add to the duration of a given project, and require more upfront work, NFC feels strongly that the results will be worth the effort.

By considering everything impacting a given stream, NFC looks to maximum our investment in time and money by yielding the highest level of benefit possible. This will also prevent NFC from spending money, your money, on expensive habitat work that will not have a positive impact or deliver on its promise.

why Trout Brook?

In order to test our methodology, NFC needed a beta project water. While picking a stream that was in relatively good shape but needed some work would have been easy, it would not have allowed us to test our theories to the degree we felt was necessary to ensure we were on the right path.

Rather than go for a sure win, NFC chose a distressed coldwater ecosystem where we are as likely to fail as we are succeed. We understand that you learn more by working in complex systems with multiple challenges than simple systems. This is why NFC chose Trout Brook in Dover, Massachusetts.

A generations old manmade in-stream swimming pool in the headwaters of Trout Brook.

Confirming whether wild native brook trout still persist in Trout Brook is an important part of the project. If not, it is a sign that something is wrong at the watershed level, as while it is easy to depress a population of fish, their complete loss is usually the sign of compound problems, not a single issue or event.

If the brook trout are gone from Trout Brook, or the population is notably depressed as it appears to be, we will try to determine why and assess whether anything can be done about it.

The Brook Trout of Trout Brook

Along with endangered Atlantic salmon, brook trout are one of only two salmonids native to Massachusetts, and the only freshwater native salmonid. Relics of the last ice age, brook trout are a sign of cold clean water, intact habitat, and a lack of competition from nonnative fish species.

Trout Brook is a unique wild brook trout stream. Unlike others that meander and tumble their way through canopied forest, Trout Brook flows through a series of large open floodplains for much of its length. It looks more like a warmwater stream than a place you would find wild native trout.

A wild native Massachusetts brook trout.

Based on historical maps, the name Trout Brook dates back to at least 1831. A 1914 state fish and game survey sheet said the “brook is full of [brook trout] fingerlings.” The quote is followed by a statement regarding its trout stocking potential, showing just how little we understood about aquatic ecosystems at the time.

A 1997 stream assessment performed by Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection referred to Trout Brook as the “coolest” stream in the Charles River watershed, and classified it as “High Quality Water.” The document also says, “although not classified as Cold Water Fishery, it does support a native eastern brook trout population.”

An August 2, 2007 Stream Survey Sheet. EBT refers to Eastern Brook Trout.

Although Trout Brook has been stocked for decades, albeit with a relatively small number of fish each year, wild native brook trout were still extant in as recently as 2007 according to MassWildlife survey data. In fact, 36 wild fish were captured in a relatively short section of the lower stream at a time of year when they can be hard to find.

Unfortunately, citizen science angling, MassWildlife sponsored e-fishing, and eDNA sampling performed at various times throughout the 2023 season and in several sections of stream failed to confirm the presence of brook trout. While this is not proof of absence, it shows that at best the population is notably depressed and possibly extirpated.

The last known evidence of wild brook trout in Trout Brook comes from a former Dover resident who fished the stream for years before moving west. He provided NFC with a short video of a small wild brook trout caught in 2009 from a small tributary in the headwaters of Trout Brook. The fish was reported to be one of several in the pool.

The last confirmed wild native brook trout from Trout Brook, 2009

a call to arms

In the winter of 2022, NFC learned that the wild native brook trout of Trout Brook might be gone, victims of some yet to be determined event, or more likely series of events occurring over a period of time. A 2020 survey of Trout Brook conducted by Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife did not yield any brook trout.

Equally troubling is that warmwater species are now present, likely the sign of warming water. Brook trout need cold water, and a minor change in mean temperature, or extended periods of warm water can result in their demise.

The possibility that these unique, beautiful and rare to the area wild native brook trout might have expired concerns us. We want to know more…

While he had not been there in 40 years, NFC Executive Director Bob Mallard used to fish Trout Brook when he lived in Massachusetts. This provided us with an invaluable historical perspective and baseline based on firsthand experience that will help assess what has changed.

Per Bob, recent pictures of Trout Brook show the once gin-clear water running a bit tannic. This could be a sign of impounding. Where there was once clean sand bottom, there is now a coat of dark silt, a sign that the stream is not flushing like it used to. This can contribute to warming as dark bottoms absorb more sun.

A virtual tour of the watershed via Google Earth shows significantly more standing water than Bob remembered. And there are water-bound standing dead trees, evidence that the stream has spread into what was once dry land or seasonal floodplain influenced by snow melt and rain events.

It is however possible, and hopeful, that the wild native brook trout of Trout Brook may still be there, albeit in reduced numbers, eking out a living in degraded habitat beyond the reach of the masses.

The Trout Brook project

The Massachusetts chapter of Native Fish Coalition, with help from Charles River Watershed Association and MassWildlife look to ascertain whether wild native brook trout still persist in Trout Brook. The group also wants to assess the condition of the coldwater characteristics of the ecosystem.

NFC and our partners will gather information and collect data to determine what is going on at Trout Brook. This will include a top-to-bottom physical stream assessment, season-long temperature monitoring, pH and chemical testing, as well as electro-fishing, citizen science angling, and eDNA analysis to try to confirm the presence of wild native brook trout and other species.

To make eDNA testing possible, MassWildlife has agreed to suspend brook trout stocking while we try to determine if wild brook trout are still extant in Trout Brook. Last stocked in May 2022, while not absolutely guaranteed, with one low-water fall, one winter, and two summers behind them, the previously stocked fish should have flushed through the system by this fall.

While it is impossible to definitively confirm the absence of brook trout, presence can be proven. We can also determine if Trout Brook is capable of supporting wild brook trout, and if not, can anything be done to mitigate the situation. The wild native brook trout of Trout Brook are important. We need to do what we can to try to save them.

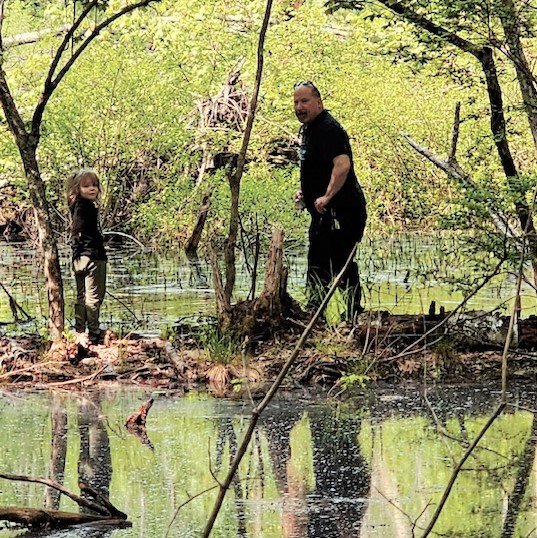

Physical assessment of Trout Brook commenced in March, 2023. The group used Google Maps and Google Earth to look at the watershed from an aerial perspective. They also studied historical maps and records. Volunteers took to the field on foot and in canoes to physically assess the stream as well. This has resulted in a detailed understanding of the physical characteristics of the watershed.

“Partnering with NFC on the Trout Brook project has given us the unique ability to rely on a diverse group of motivated and talented citizen scientists to gather a large amount of information and data on a level that we are rarely able to attain on our own and on such a short timeframe. Developing a complete picture of the Trout Brook system will help us to identify, and hopefully remedy, the issues that are currently limiting the wild Brook Trout population.”

floodplain

Historically, Trout Brook flowed through a long, wide and expansive floodplain. This served to regulate flows during high-water periods. While Trout Brook flowed clear and cold throughout the season, the area around it rose and dropped with spring snowmelt run-off and rain events.

Much of the Trout Brook floodplain was a hummock field with live brush and trees interspersed along mud-bottom channels that acted as temporary storage during high-water periods. The construction of roads a century ago as well as a gas line later altered the floodplain in several ways.

Roads built across Trout Brook fragmented the historic floodplain. Water upstream of the roads rose due to notably undersized culverts and the loss of continuity. Downstream of the roads, especially Haven street, the upper end of the floodplain dried up due to the quickened and channelized release of water.

The floodplain on Trout Brook disrupted by roads and a gas line (top left to bottom right).

In places, the floodplain was narrowed by the construction of berms to house gas pipe lines. This lessened the floodplain’s ability to store water, and caused the seasonal and event water level to rise above normal where berms encroached on the wetland. It also fragmented the floodplain n one point due to a crossing. In addition, the berms likely interfered with surface water tributary inputs.

SPRINGS

The area around Trout Brook is rich in springs. It was originally called Springfield Parish, and one of the three primary road crossings is called Springdale Avenue. And as noted earlier, Trout Brook was referred to as the “coolest” stream in the Charles River watershed in a 1997 stream assessment report.

Close to 70% of the homes in Dover get their water from private wells. Most others rely on local ground water provided by a public water supplier. The area has experienced drought conditions, causing wells to fail and reducing groundwater supplies.

dams and stream crossings

Trout Brook did not escape the colonial dam building era. While only one notable dam remains, apparently built to power a small grist mill, it separates the headwaters of Trout Brook from the rest of the stream from a fish-passage standpoint. Two small dams said to have been built to create an in-stream swimming pool may block fish passage as well. And all three could be causing some level of thermal stress.

A century old stone dam on upper Trout Brook.

Like most streams in the east, Trout Brook has been altered by the construction of roads, rails and other infrastructure. There are eight improved road crossings, and nine unimproved road, rail and gas line crossings. All have some form of bridge or culvert. Due to their age, most of the crossings in the Trout Brook watershed inhibit stream flow to at least some degree, and in some cases, to a high degree.

beavers

Beavers and brook trout have coexisted in relative peace for as long as the two species have overlapped. While nothing outside of man alters their habitat more, the impact of beaver on watersheds, riparian areas, wildlife and fish is both good and bad, and short-term and long-term.

Fishers, otters, coyotes, lynx, bears, mountain lions, wolves, and even owls, hawks and eagles prey on beavers to some degree. But the most effective predator is said to have been wolves, a species extirpated from Massachusetts over 150 years ago.

While recreational trapping filled the void left by the loss and reduction of natural predators for decades, a decrease in fur prices as well as a law passed in Massachusetts in 1996, the Wildlife Protection Act, have allowed beavers to attain what appears to be an unnaturally high abundance in the Trout Brook watershed.

fish

Trout Brook is not your typical coldwater ecosystem. In addition to being a native brook trout water, it was also home to cool water species such as redfin pickerel, white sucker, and tessellated darter, as well as warmwater species such as yellow perch, banded sunfish and pumpkinseed.

Redfin pickerel (Esox americanus americanus) prefer moving water and slightly cooler temperatures than the more common chain pickerel (Esox niger).

As a result of introductions done in support of recreation, the trout Brook watershed is now home to self-sustaining populations of nonnative largemouth bass and bluegill. Golden shiner are present as well, and while native to the state may not have been native to Trout Brook.

TEMPERATURE MONITORING

Brook trout need cold water to survive. While they can tolerate water temperatures over 70 degrees for short periods, the ideal mean temperature is between the low 50s and the mid 60s. Streams can warm due to damming, groundwater use, drought, changes to the weather, and even excessive beaver activity.

NFC and our partners look to monitor the temperature at various locations throughout the Trout Brook watershed for a full season to ascertain if there are any notable thermal stress contributors. If anything notable is identified, we will report what we found along with what if anything could be done to mitigate it.